We visited Chillion Castle (Château de Chillon), on our way to Gruyères from Zermatt. On the way, we passed through Martigny.

Now there are castles and castles in Switzerland. But what distinguishes the Chillion Castle in addition to its unique location is its history, shape, layout, architectural features and interestingly, its place in popular imagination, as reflected in its association with intellectuals – thinkers, writers and painters – of the Romantic Period of early 19th century Europe.

First thing first – the location.

The easiest way to reach the Chillion Castle is by a train, to the well connected town of Montreux. From Montreux, you can take a bus, that will drop you in front of the castle, in less than 10 minutest. The other and better alternative, if you have the time, is to walk from Montreux to the Castle, along the banks of Lake Geneva (Lac Léman, as the French call it). It is a 45 minute leisurely walk and all along the way, you get stunning views of the lake and the Alps, at a distance.

The castle is located on a small, rocky outcrop on Lake Geneva just off the shore, at the foot of the looming, snow-capped Alps; it feels as if the castle has risen straight out of the lake. The aquamarine, crystal clear waters of the surrounding lake and the pristine white snow capped Alps at a distance provide perfect setting to this stately man-made structure. The location couldn’t be more dramatic, giving this castle a totally fairytale look.

Now a about the history of this castle*.

There is some archaeological evidence to suggest that this site was fortified since the Roman times. However the oldest structure that we can see today is from circa 1150 CE, built by Thomas I of the Royal House of Savoy in France.

It is worthwhile to note that the Chillion Castle wasn’t built in one go. At the same time, it is not clear exactly when the foundations of the castle were laid. As we see it today, it is a complex collection of over twenty five or so odd buildings and over forty rooms, interlinked by an equally complex and ingenious network of internal and external passages and causeways. The present structure represents over eight centuries of construction, improvements, renovations, restorations and adaptations, interspersed by periods of neglect and decay.

The rocky outcrop on which the castle is located, served as an ideal defensive promontory for the Savoys. Because of the barrier posed by the lake, it was difficult for enemies to break through into the castle. On the other hand, proximity to the shore made it easy for troops from the castle to be easily deployed if needed.

From 12th to the 16th century, the Counts of Savoy held the castle. Because the castle faced the road (the ‘Via Italia’) to the St. Bernard Pass, connecting Burgundy (in France) and Italy, it was instrumental in protecting the military, political and economic interests of the House of Savoy. It controlled one of the principle access routes for trade (linking north and south of Alps) and could regulate import and export between Italy and North Western Europe and also earn revenue through tolls. The castle also controlled the movement of ships on Lake Geneva.

In its heydays, Chillion Castle was therefore a strategic, administrative and financial centre for the Savoys.

Much of what we see of Chillion Castle today is from circa 1235 CE, when Peter II of Savoy expanded the older structure and commissioned many of the castle’s notable features, namely the gentle lakeside façade and three stylized, pointed towers on the opposite side.

In addition to being an occasional residence of the Counts of Savoy, the castle was also used an arsenal and prison. The Counts did not live in the castle always because they led a largely nomadic life – more often than not travelling on military campaigns or attending to governance and administrative affairs of their extensively spread out territory. They were pretty hands-on rulers.

Needless to say, the Count travelled in style and grandeur. Apart from his close circle of family and friends, his entourage was made up of his personal army, administrators and retinue of servants. And along with him, also went some of his furniture and equipment so that he could stay in comfort wherever he pitched tent. The rooms in the Chillion Castle were therefore largely empty and locked when the Count was not in residence.

The castle had its resident Governor – the Castellan responsible for operation, maintenance and security of the castle. The Castellan was also responsible for dispensing justice and levied customs duties on behalf of the Count. He was a member of the Savoy aristocracy.

However, by the end of the 14th century, the Savoys seemed to have largely lost their interest in the castle and moved their administration to Chamberly. The castle fell into neglect and stared being used mainly as a prison from then onwards. The grip of the house of Savoy further diminished as they became intolerant and took rash political decisions. They imprisoned and tortured their political rivals.

In 1536, there was an uprising against the Savoys and taking advantate of the situation, rival Bernese troops stormed the castle, freeing prisoners from the dungeon. The German speaking Bernese controlled the castle between 1536 and 1798, during which it served as a fort, arsenal, storage and prison and the residence of the Bailiff, a member of the Bernese monarchic administration.

As a final outcome of the Vaudous Revolution in 1798, the Canton of Vaud was founded in 1803. Chillion Castle thereafter became, and quite rightly so, the property of the French speaking Swiss canton of Vaud.

One can therefore see distinct influences on this castle as it was rebuilt, renovated and expanded over different phases of its occupation.

So much for the location and history of this castle, now about the castle itself, as we saw it.

We entered the castle, walking over the beautiful covered wooden bridge that led to an arched gate, into the lower courtyard of the castle. Earlier, there was a drawbridge over a moat (part of the lake) and we saw the pulley system that remained from the drawbridge. In the lower courtyard, towards the left, we found an incredibly beautiful drinking water fountain.

Chillion Castle had an unusual and very beautiful elliptical layout and this was unlike other Savoy castles that followed a square plan with circular towers at each corner, connected by bastions. This castle, despite being quite formidable, had harmonious, non linear lines and soft elements that were aesthetically very pleasing. The curved bastions and sentry walks were interspersed by soaring, stylized circular towers with pointed conical roofs.

Chillion Castle had an unusual and very beautiful elliptical layout and this was unlike other Savoy castles that followed a square plan with circular towers at each corner, connected by bastions. This castle, despite being quite formidable, had harmonious, non linear lines and soft elements that were aesthetically very pleasing. The curved bastions and sentry walks were interspersed by soaring, stylized circular towers with pointed conical roofs.

And as mentioned earlier, the buildings and rooms were interconnected by a complex of passages and corridors. We took an audio guide, but you also have a user-friendly brochure that you can follow for a self guided tour of the place.

The first place we went to was the high vaulted, subterranean dungeon, cut into the bed rock. The dungeon was supported by seven large pillars that created two rows of eight vaults, with intersecting ribs. The pillars, arches and the ceiling of the dungeon were distinctly Gothic in plan and design. In addition to diffused sunlight beaming in at places, the place was also specially lit up in a pretty successful attempt to create an ominous and brooding atmosphere.

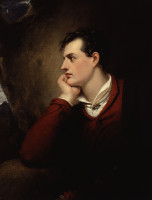

We saw the place where political prisoners were chained. The most celebrated political prisoner was François Bonivard (imprisoned from 1519 to 1521) about whom Lord Byron wrote a famous poem in the 19th century. Bonivard was the Prior (an official of a monastery, below the Abbot) of Saint Victor in Geneva and a political activist of his times. He was a partisan of the Protestant Reformation movement and sided with the patriots of Geneva who opposed the Savoy.

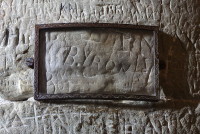

There was a place on the wall (now protected by a glass casing) where Lord Byron had crudely etched his name on the stone. I was rather amused by this graffiti. After all he wasn’t a prisoner there – he merely wrote a poem on one.

There was a place on the wall (now protected by a glass casing) where Lord Byron had crudely etched his name on the stone. I was rather amused by this graffiti. After all he wasn’t a prisoner there – he merely wrote a poem on one.

There was a narrow emergency escape (The Postern) from the dungeon, into the Lake. A staircase connected the dungeon with the floor above where the rooms of the castle were situated. This was the route used by Antoine de Beaufort , the Savoy officer in charge of the castle, to flee via the lake, when the Bernese stormed the castle in 1536.

We emerged out of the Dungeon back into the lower courtyard and then proceeded to the Castellan’s courtyard – the space used by the governor of the castle. And from there we went further ahead, into the largest and grandest courtyard – ‘The Courtyard of Honor’ – a space designated for use by the Counts and their retinue, for ceremonies and small parades.

We then decided to take a tour of the interiors. Of the many rooms in the castle, four were the ‘great halls’ with large impressively decorated windows overlooking the lake. The oak pillars and ceilings of these rooms were executed in dark wood, and the wood work was elaborate and beautiful.

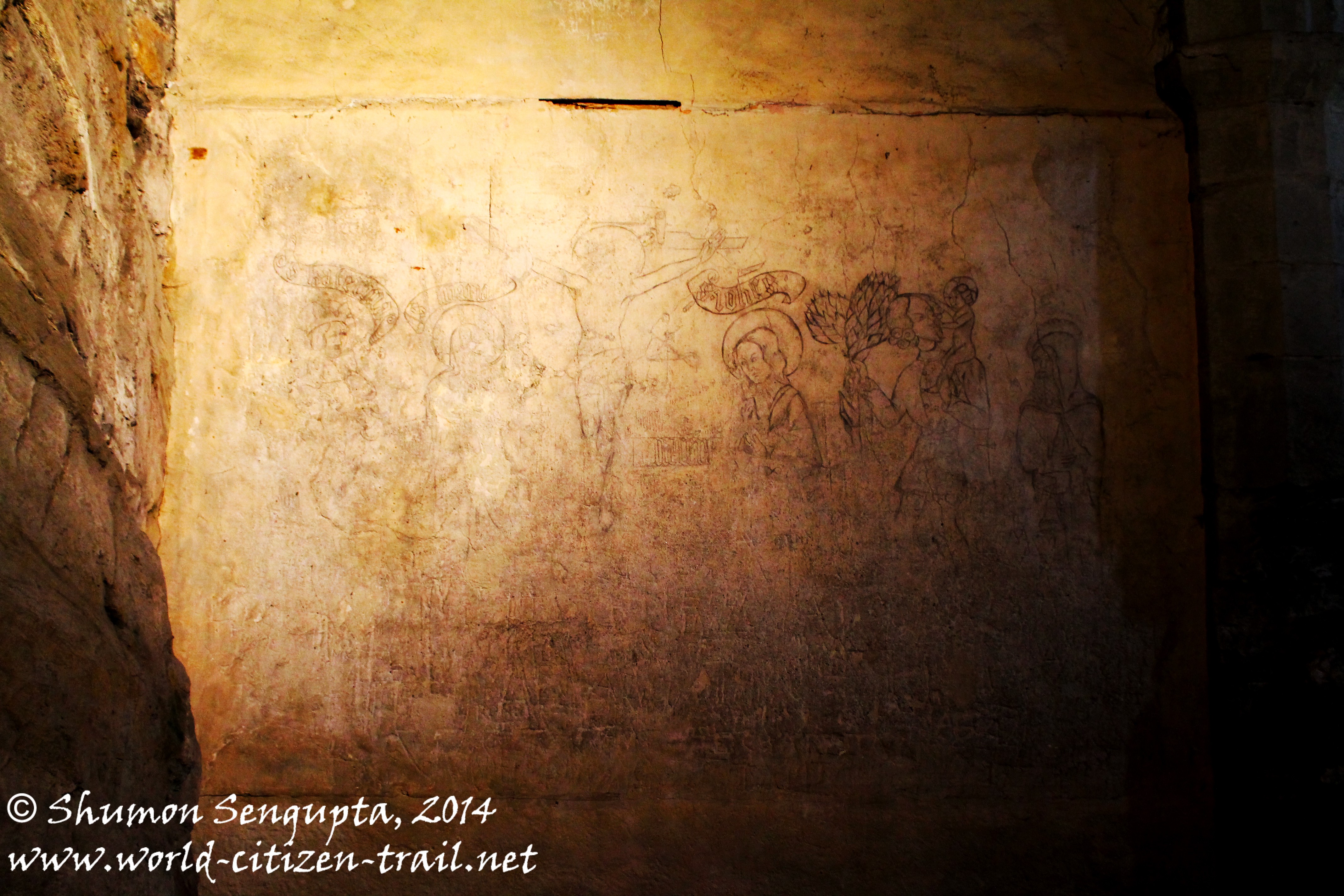

During the Savoys, grand banquets were held here and we found details of what the Savoys feasted on, in one of the information boards inside the banquet hall. The feast was enormous, to say the least.

I read from the information board that the ingredients of a typical banquet, which lasted several days, included 100 oxen, 130 sheep, 100 piglets, 60 fat pigs, 200 kids, 200 lambs, 100 calves, 2,000 heads of poultry and 6,000 eggs. To that were added products from hunting – venison, hare, partridges, cranes, herons and other wild birds. For those who did not eat meat, particularly men from the Church, various fish / sea food were served: dolphins, mullets, sole, hake, sea bream, turbot, sturgeon, salmon, eel, trout, carp and perch.

A veritable lesson in Zoology, I thought.

Spices, of exotic origin and therefore precious, were considered as basic ingredients. For seasoning, it was therefore necessary to have ginger, cinnamon, Guinea grains, pepper, nutmeg, cloves, mace, galingale and saffron.

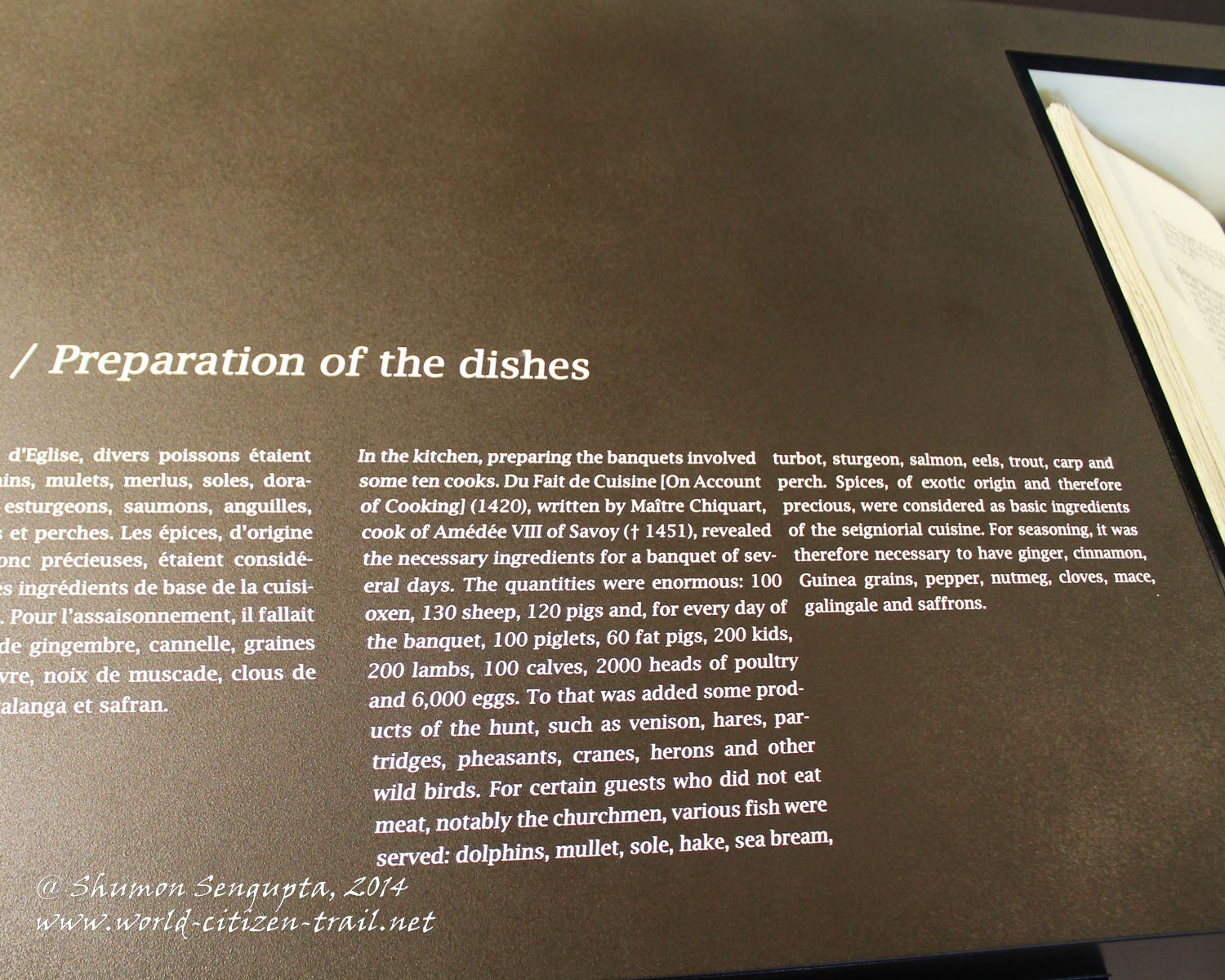

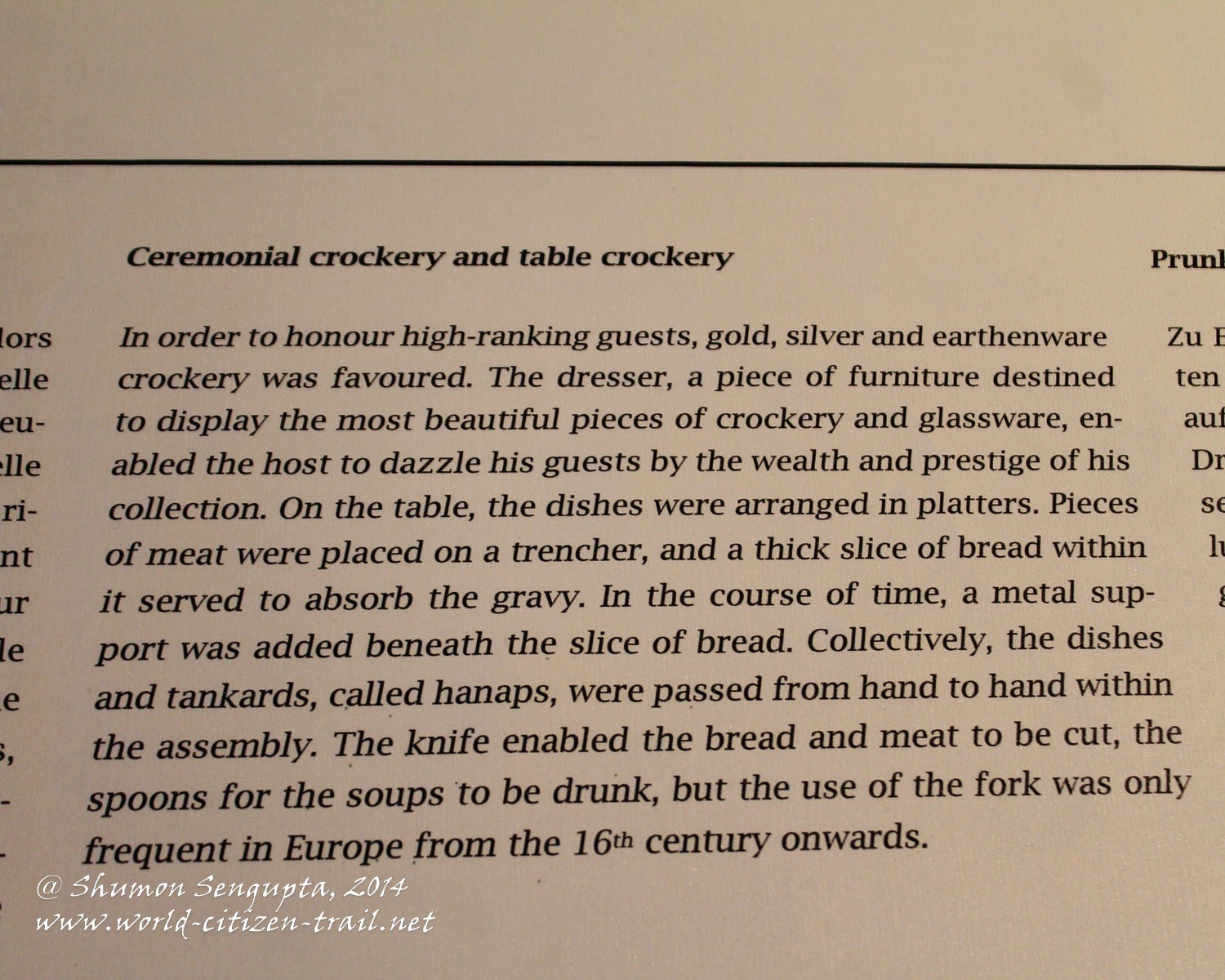

There was also an impressive list of kitchen utensils and crockery used. But I shall not waste my time writing that out and include a couple of photographs (of the information board) instead.

The modest furniture collection of Chillion castle included 80 chests and cases, 40 tables, 140 seats and 25 cupboards/sideboards.

We also saw an amazing exhibition of medieval chests (mostly reproductions) in one of the grand rooms.

The grand rooms these days are let out for seminars, exhibitions and receptions. We found the largest one (the Great Hall) booked for a Chinese (sic) wedding reception and there was a group of Swiss Alphorn players commissioned to welcome guests. Very interesting, I thought.

The bedrooms were comparatively modest, with the most notable one being the Camera domini, used by Count Aymon of Savoy.

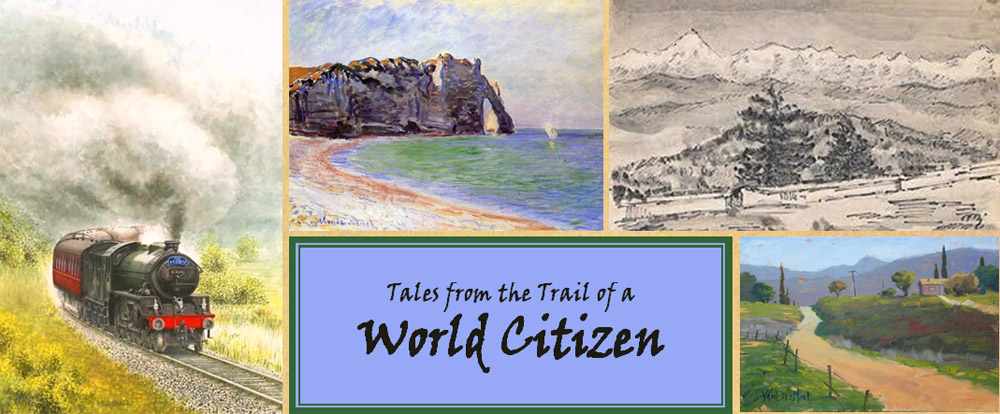

In 1341, this bedroom was decorated in elaborate frescoes, by painter Jean de Grandson. Although in bad condition because of age, we could nevertheless make out the grandeur of the frescoes, from what little remained today. Apart from a heraldic frieze, abstract decorative and floral patterns, there were images of trees and grassland, lion, leopard, deer, wolves and gazelle and two fantasy animals – a griffon and a dragon.

And there was also the Bernese Chamber. It has a high four-poster bed, room heating and an attached private toilet that had running water – a luxury in those days. And there were beautiful minimalistic frescoes of vines, fruit and birds and abstract decorative motifs, painted high up on the wall.

There was a spiral stairs that led from the private quarters directly to the private chapel. We visited the beautiful chapel through a different access route and admired what remains from some beautiful 14th century frescoes on the Gothic ceiling.

There was a spiral stairs that led from the private quarters directly to the private chapel. We visited the beautiful chapel through a different access route and admired what remains from some beautiful 14th century frescoes on the Gothic ceiling.

The Castellan’s dining hall had beautiful frescoes of family crests.

And one of the most curious aspects of this castle was the system of medieval toilets. The lake facing side of the castle had numerous ‘garderobes’ or toilets – small alcoves/antechambers with wooden potties (basically a wooden bench with a hole) that, in the absence of a sewerage system, opened directly on the lake below. Contents of the toilet fell from great heights, directly into the lake! And in one of these toilets, we found two potties side by side – obviously privacy wasn’t a big deal then.

And then there was a full exhibit dedicated to the details of toilet habits in the medieval age – a period when only the most privileged had access to private bathrooms and fresh water. Needless to say, someone with a sense of scatological or toilet humor would have a field day here.

The last place we went to was the Keep or storage, which was linked to the other buildings through long sentry walks and ramparts. It was a long climb up through a series of steep stairs, to the top of the tower. Along the way we saw impressive displays of medieval weapons. The last section to the top of the tower was through a wooden ladder and one had to be fairly sure footed to negotiate this. But then if I, with my severe fear of heights could do it, so can anyone else.

At the top, we saw aerial views and aspects of the castle were revealed, which were not visible from any other point; climbing all the way up was therefore worth the effort.

We got down and spent some time walking over the sentry walks and ramparts, from where we got more aerial views of layout of the castle, the courtyards, battlements and some of the interconnecting passageways.

There are two distinct but closely connected facets, rather facades of the castle.

The side facing the mountain and the road (Via Italia) was the vulnerable side and hence designed as a proper defense fortress: with a moat and drawbridge, double ramparts, sentry walks, machicolations (narrow slits through which rocks and boiling oil could be dropped on attackers below on the battlements) turrets and watch towers – everything that was needed to thwart enemy attack from land.

On the other hand, the façade facing the lake was built like a palace, with beautiful Gothic windows and luxuries worthy of royal residence. The simple and elegant façade on the lake side was bereft of any defensive walls or fortifications and provided a total contrast to the side facing the road and the mountain.

And finally, about the lure of the Romantics to the Chillion Castle.

In the 19th century, Chillion Castle became a favorite of Romantic intellectuals of the times. These writers and painters were drawn to the castle, not just for its location and beauty, but also because it presented an antithesis to the follies and foibles of rapid industrialization and mechanization society was witnessing in general.

While in 1762, the castle was featured in an episode in Rousseau’s sentimental novel – La Nouvelle Heloise, in the 19th century, Chillion Castle provided inspiration to writers like Victor Hugo and Gustav Flaubert and to painters such as Victor Eugène Delacroix and even the realist painter, Gustave Courbet.

And then, as mentioned earlier, Lord Byron, the eminent English Romantic poet wrote “The Prisoner of Chillon Castle” – a long poem narrating the plight of political prisoner, François Bonivard. This narrative poem is replete with the image of a man standing up against injustice and then suffering in isolation in a dungeon, with imaginary visions of the beauty of nature giving him solace.

And then, as mentioned earlier, Lord Byron, the eminent English Romantic poet wrote “The Prisoner of Chillon Castle” – a long poem narrating the plight of political prisoner, François Bonivard. This narrative poem is replete with the image of a man standing up against injustice and then suffering in isolation in a dungeon, with imaginary visions of the beauty of nature giving him solace.

In Byron’s poem, this rather controversial historical figure (Bonivard is considered a libertine in many accounts) became an exaggerated symbol of liberty and his prison invested with almost sacred attributes. Clearly, the Chillion Castle and its high profile prisoner of the 16th century provided potent ingredients for literary output to our celebrated Romantic poet of the 19th century.

In many ways, for me, it was not surprising that the Chillion Castle become so popular with the intellectuals from the Romantic period. The location couldn’t have been more appealing and relevant to the mood: rigid stern brown walls, ramparts and towers and a disturbing history of a fairytale like castle contrasted with the soothing and soul stirring beauty of nature – the vast blue waters of the placid lake and the backdrop of majestic, pristine snow capped mountains.

By all means, Chillion Castle is an architectural jewel because of its shape, form, style and harmony of lines, in addition to being located in one of the most incredibly beautiful settings one can think of.

This was a place in which Nature was seen by the Romantics as an antithesis; a counter balance to the follies of the industrial age. It was a place that resonated deeply with the sense of aesthetics and a romantic vision of the past they held so dear – an appeal that endures and continues to enthrall visitors like us even to this day.

*Reference: “A walk around the Castle of Chillon“, Claire Huguenin, Fondation du Château de Chillon, 2008