From various historical accounts, folklore and religious texts, it appears that very fine fabrics were available in Bengal as far back as the first century BCE. Once such celebrated fabric of the subcontinent is the Jamdani of Dhaka (present day Bangladesh). The Jamdani weave as we see it today is essentially a fusion of the ancient weaving techniques of Bengal which is around 2,000 years old, with the gossamer like “Muslin” produced here since the 14th century. The Jamdani weave therefore represents over two thousand years of continuous aesthetic evolution that blends different artistic influences.

From various historical accounts, folklore and religious texts, it appears that very fine fabrics were available in Bengal as far back as the first century BCE. Once such celebrated fabric of the subcontinent is the Jamdani of Dhaka (present day Bangladesh). The Jamdani weave as we see it today is essentially a fusion of the ancient weaving techniques of Bengal which is around 2,000 years old, with the gossamer like “Muslin” produced here since the 14th century. The Jamdani weave therefore represents over two thousand years of continuous aesthetic evolution that blends different artistic influences.

In the “Arthashastra” – a book of economics written by Kautilya around 300 CE, we find the earliest mention of Muslin/Jamdani, where it is stated that this fine cloth used to be made in Bengal. There are indications that Muslin/Jamdani was an established industry at that time. Its mention is also found in the book of Periplus (of the Eritrean Sea) and in the accounts of Arab, Chinese and Italian travellers and traders, who, it may be safely speculated, took the fabric much beyond the borders of Bengal. In the 14th century, Ibn Batuta profusely praised the quality of cotton textiles of Sonargaon. Towards the end of the 16th century the English traveller Ralph Fitch and historian Abul Fazl also praised the Muslin made at Sonargaon, outside Dhaka.

Muslin is a light cotton fabric, finely woven and typically white, that was first imported from the Middle East to Europe in the 17th century. It is named after Mosul in modern-day Iraq, the city through which it made its way to Europe. Dhaka and Masulipatnam (in south India) were the two most important centres for the production of Muslin. By all accounts, Dhaka however can be considered as the fabric’s true place of origin, from where it was exported to the rest of the world.

At its best, the Muslin was so light and fine that one yard of this fabric weighed barely 10 grams and a full six yards of the fabric could pass through a ring of the index finger. In 1840, Dr. Taylor, a British textile expert, wrote: “Even in the present day, notwithstanding the great perfection which the mills have attained, the Dhaka fabrics are unrivalled in transparency, beauty and delicacy of texture.” The Muslin was legendary because a 50 metre long Muslin fabric could be squeezed into a match box!

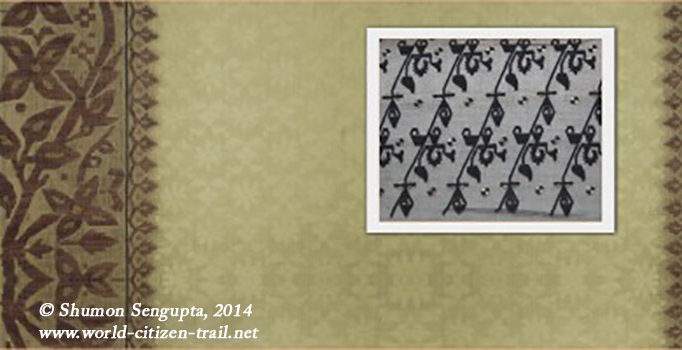

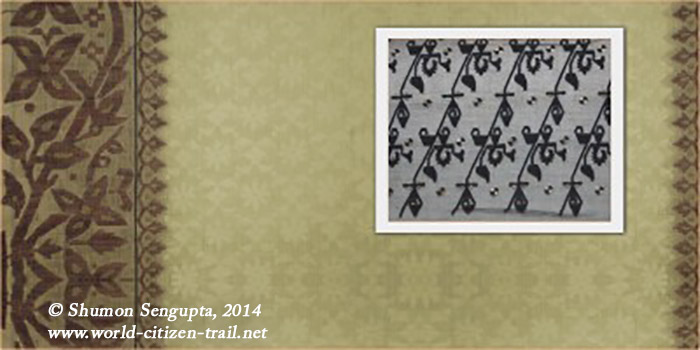

The Dhaka Muslin serves as the base fabric into which the elaborate and ornate patterns of Dhaka Jamdani are woven. In a Jamdani, a single warp is usually ornamented with two extra weft (thereby creating the design) followed by ground weft. The Jamdani is therefore an inlay technique on lightweight cotton fabrics. Jamdani essentially introduces a thick thread work into a Muslin base to weave various patterns. Hence Jamdani can be called the “figured” or “embellished” Muslin. Jamdani weaving is akin to tapestry work, where small shuttles of thick coloured, gold or silver threads are passed through the weft to create designs on the plain base.

According the Chandra Shekhar Saha, a Bangladeshi textile expert, Jamdani is unique mainly due to two reasons. Firstly, it has distinctive and consistent use of geometric patterns that are inspired by Iranian motifs. Secondly, the opacity of the pattern woven into the transparent base mesh together during the weaving process in such a way as to make the Jamdani look supremely delicate, fine and beautiful. Though apparently the motifs used in Jamdani have an abstract look, these are actually the creative and geometric transformation of nature’s elements such as creepers, leaves, flowers, animals etc. The predominance of Iranian motifs in Jamdani is attributed to the later day Mughal influences on the evolution of the aesthetics of the weaving tradition.

Muslin and Jamdani reached their pinnacle of excellence during the Mughal period (16th to 19th century). In this period Jamdani was used extensively in “angarakhans” or attire for both women and men. At the same time, the use of Jamdani fabric was seen in women’s dresses in Europe’s capitals of fashion. From the middle of the 19th century, there was a gradual decline in the Jamdani industry. A number of factors contributed to this decline. Use of machinery in the English textile industry, and the subsequent import of lower quality, but cheaper yarn from Europe, started the decline. Most importantly, the fall of Mughal power in India, deprived the producers of Jamdani of their most influential patrons.

Presently, the Jamdani industry is struggling to survive in approximately 150 villages of Rupganj, Sonargaon and Siddhirganj, under Dhaka district. Barely an hour and half drive from Dhaka, situated on the bank of the river Shitalakhya is the village Ruposhi – popularly known as the Jamdani village. As you enter the village, you come across weavers who are busy at the looms, creating – probably the most exquisite handloom weaves in the world. Men, women and children of the village are all involved in some stage of the production process. Most adult weavers work as long as 18 hours a day with breaks for meals or prayers. The work itself is very laborious and requires extreme concentration.

These expert weavers can create the design mentally during the weaving of the saris. There is no mechanical technique involved. Jamdani weavers have remained largely illiterate or semi-literate. However, despite the lack of any primary education in its formal sense, the mental faculties of the weavers are as sharp as mathematicians. How so ever complex the pattern might be, it is imprinted in the minds of the master weaver and passed down from generation to generation through apprentices who eventually, through years of toil, become master weavers. There are no written documents for the innumerable motifs used in Jamdani. The motifs are repeated with remarkable precision and there is hardly any inconsistency in the design. Nothing is sketched or outlined. The weavers just know the exact number of times to do a certain stitch to combine the yarns to come up with a particular motif.

At present, a major problem of the Jamdani industry is that the weavers do not get adequate wages for their labour. A senior weaver earns about Tk 4000 (USD 60) in a month. Junior weavers get much less, around USD 20 per month. As a result many weavers do not want their children to take up this profession. For many, the readymade garments industry offers a lucrative alternative. A good piece of Jamdani sari needs the labour of two to three months, and the wages paid to the weavers do not compensate for their labour. The producers often do not have direct access to sari markets and because of their dependence on the middlemen, who often form informal cartels; they are deprived of their share of profit. Sometimes, the producers fail to recover the costs.

The government and other organisations are however trying to revive the old glory of Dhaka Jamdani. In a bid to avoid the middleman they have established direct contact with the weavers. A Jamdnai Production Centre (Jamdani Palli) has been established near Dhaka. Jamdani is also being revived due to the pioneering and tireless work of individuals like Ruby Ghuznavi, Monira Emdad and Tamara Abed. Ghuznavi runs Aranya – an exclusive outlet in Banani, Dhaka, specialising on Jamdani, using natural dyes. Emdad runs Tangail Saree Kutir on Baily Road in Dhaka. Important organisations that are trying to revive Jamdani are Aarong (whose outlets are located in major cities of Bangladesh) and Kumudini (which has a big outlet in Gulshan, Dhaka).

Ruby Ghuznavi has successfully revived old designs and Aranya is doing a lot of work on product development, transferring Jamdani onto clothing materials for women and men.

Aarong – the leading local fashion house – has been contributing to the revival of the Jamdani in a major way. Led by Tamara Abed, Aarong has been promoting Jamdani by showcasing the magnificence of the weave through its exhibition called the “Story of Pride”. This is in addition to the support that Aarong provides to hundreds of Jamdani weavers by working with and marketing their products throughout Bangladesh.

Jamdani industry, which is nothing less than “high art”, can only survive if the market is expanded within Bangladesh and outside. Jamdani needs to be made more popular among the privileged classes while ensuring that the quality and artistry of the weave is maintained. Unless the demand for Jamdani saris, dresses and furnishing materials (the fabric is now also being used for making curtains) is increased, weavers will continue to suffer in terms of lower wages. Worse still, is that their children will not find it feasible to enter into a profession that pays so little in return.

A two millennia old heritage, with its highly evolved aesthetics, faces extinction unless it can be popularised and promoted across the world. Jamdani is not just a heritage of Bangladesh, it is truly a global artistic inheritance that needs to be preserved and promoted.