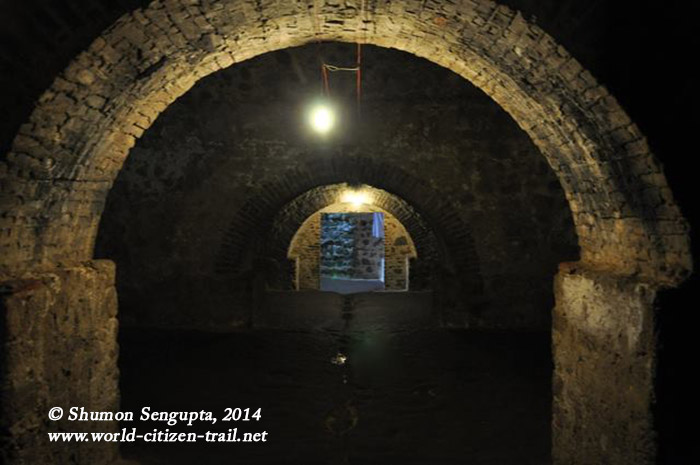

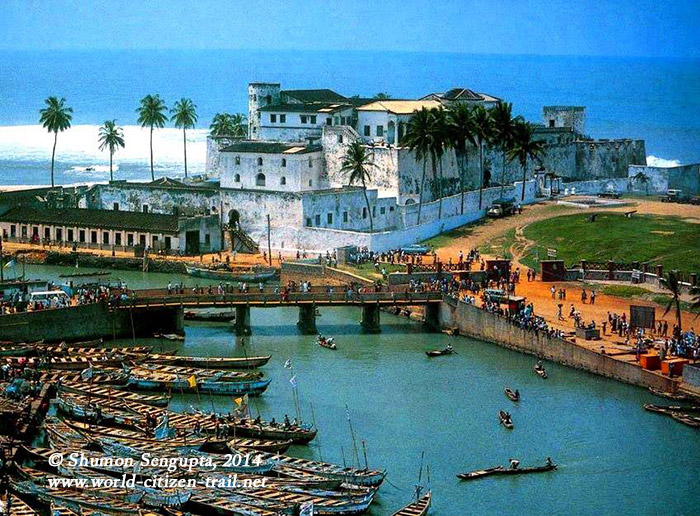

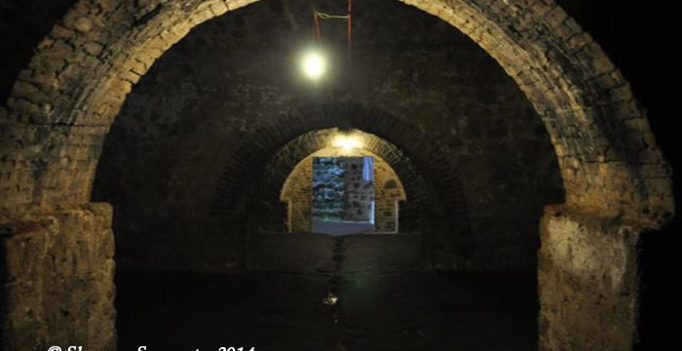

In the previous two episodes from my trip to Ghana, I wrote about the history of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade that spanned over four centuries and how the coast of present day Ghana (erstwhile Gold Coast) came to be the hub of this trade. We also traced the footsteps of the slaves in the Cape Coast castle. In this concluding episode of a three part series, I shall take you along to the Elmina, also known as the St. George Castle, the oldest and grandest from that period – a Castle that witnessed over four centuries of colonial trade in gold, ivory, timber, spices and slaves. The mute cold stones and walls of the castle indeed have tales to tell, but then only to those who are keen to hear, not through their ears, but with their hearts. I invite you to come along with me on this amazing journey into the past. Driving from the Cape Coast castle along the road that roughly parallels the coconut palm fringed shores; I arrived at the busy and vibrant fishing town of Elmina. Along the way, on the sea side by the road, I saw carpenters building traditional, colorful wooden fishing boats and Pirogues in open air workshops and was fascinate by the unfinished hulls which were carved out of a single piece of a gigantic tree. At the distance, amidst the coconut palms, I caught glimpse of the majestic Elmina Castle, jutting out into the ocean. Before I went into the castle, I took a brief tour of Elmina town, mainly to its fishing zone adjacent to the castle. It was an experience of its kind. Congested, noisy, energetic, colorful and terribly smelly; the fishing zone has a fascinating atmosphere with hundreds of colorful fishing boats moored at the beach – adding the element of cheer and flamboyance to the scene. I noticed that as soon as the fishermen came back to the dock from the sea with their catch, there was an eruption of spontaneous jubilation and animated applause from women and men waiting eagerly on the shore, to receive catch fresh off the boat. I understood it as a ritual – delightful and boisterous. After the fishing boats docked, complete chaos ensued. But before I realized it fully, amidst the cacophony and mayhem and apparent disorder and confusion, by some mysterious order of things, the catch was swiftly and deftly divided up and distributed amongst the women and financial transactions concluded. The women then packed the fish on large metal tubs, hauled them on their heads and carried them to the market. After spending some time there at the fishermen’s dock, I ventured into the market, where I found a wide range of sea food – fresh and processed (smoked/salted/dried) being sold. It was way too smelly for me and I found my way out of the place quickly. Beyond, I walked along the streets, passing by grand albeit decaying buildings from their colonial past, interspersed with shanties. All around, I found brisk movements, hectic activity, music blaring from radios and loud speakers, colorful sights, sounds and smells – working people in high spirits, full of vitality and a zest for life. Crossing the rickety iron bridge that separated the castle from the town, I made it to the forecourt of the castle, where a vertical line of coconut palms stood in visual contrast to the whitewashed, horizontal lines of the castle. I crossed the suspended drawbridge over the moat, now dry, through a series of passages into the inner courtyard of the castle. The Elmina castle in the Cape Coast region of Ghana is over 500 years old. Originally built in 1482 by the Portuguese as a trading post, the castle became one of a chain of establishments that served the trans-Atlantic slave trade for over 400 years. It was the first trading post in the region – the oldest European building in existence in the sub-Saharan region. Given its increasing importance in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, after a series of failed attempts, the Dutch finally succeeded in wresting the castle from the Portuguese in 1642 and then continued to use the castle as their hub for the slave trade till turn of the 19th century when slavery was finally abolished in Europe. Most of the slaves from this particular castle made their way into Brazil, then a Portuguese colony. In 1872, as an outcome of the Anglo-Dutch treaties signed between the two imperial powers, the castle went under British ownership. The fate of the castle therefore mirrored the changing fate and fortunes of the European colonial powers over the years. Occupying about 2.3 acres of land, this huge four storied castle is built on a solid foundation of sedimentary bed rock, at the edge of the North Atlantic Ocean. The site of the castle is strategically located at the end of a narrow outcrop, with the Benya River Lagoon to the left and the Atlantic Ocean in the front and the right. On the lee side of the outcrop, the natural harbor provided a sheltered anchorage for slave ships in the bygone era. The Elmina fortress was modeled on the late medieval European castle with a moat and its defenses were built to carry a large number of cannons. During its heyday, the castle was equipped with over 100 cannons and had extensive logistic support to ward off enemy attack and to hold a thousand captive slaves at any point in time, in the dungeons in the basements. Sprawling and rectangular in shape, the castle has bastions on the four corners and a curious box like church in the middle of the courtyard. The layout of the castle is broadly divided into three courtyards – the main courtyard, the inner courtyard and a service courtyard. The main courtyard had the cells for female captive slaves. The castle was built to have two large fortified enclosures and a network of residential quarters, offices, workshops, storerooms, cells and dungeons, open spaces for the operations of artisans and the military and large underground water cisterns to store rain water. The indoor spaces now remain largely empty. In the past, disease and death, particularly from Malaria, Cholera and Yellow Fever were very high and European men generally came unaccompanied. Captive female slaves were therefore regularly abused by their captors for their pleasure. In case of the governor, he stood on the balcony of his quarters high up and commanded the female slaves from the dungeons below to be paraded in the inner courtyard. He then took fancy to a particular woman and after he indicated his selection, the hapless woman was stripped and given a thorough wash by the soldiers in the middle of the courtyard. After that she was clothed, fed and sent through a flight of wooden staircase that led from one of the female slave cells, through a trap door, directly to the living quarters of the Governor. Enslaved in body, this often ensured that the women as well as other captors were broken in spirit as well. Later the woman was sent back to the dungeon below and subsequently, another woman would take her place. Women who became pregnant were freed, settled in houses outside the castle and the children of mixed race were given European names and given an education in schools run especially for them. Eventually they would grow up to become middlemen between African and European merchants, thereby perpetuating the cycle of human trafficking and exploitation. As in other castles and slave forts, captive men and women were locked up in separate dungeons – dark, damp, airless and windowless, with up to 400 men packed in each cell. Captive slaves had to relieve themselves in trenches dug along the four walls of the cell and one can only imagine the living hell it was with the smells of human waste, urine, vomit and blood mingling with humid and musty air. The captives had to sleep in the very place and at best had straw mats to sleep on. Outbreaks of malaria, cholera and yellow fever were common. Over a century has now gone, that slave trade came to an end and the place is cleaned regularly, giving us barely any idea of what happened in the past. Yet, I could feel the suffering in the air, it was so deeply disturbing. From the courtyard, I approached the “Condemned Cell”, with the sinister marking of the skull and cross bones. The “Condemned Cell” was a cramped chamber where those who resisted or rebelled were imprisoned without food or water. Most died out of suffocation and starvation and that served as a deterrent to other captives. The dead, it is said, were thrown into the ocean with stones tied to their bodies. Barely a few seconds inside the small chamber gave me a sense of being buried alive in a sarcophagus. I noticed scratch marks on the walls and I was told that remnants of human nails, skin and blood have been detected on the walls and the floor – evidence of the horror and the desperate struggle of the captives. I could faintly hear some visitors weep in the darkness. I choked and had to fight back tears – it was so deeply unsettling. Like I had done at the Cape Coast castle earlier, I walked through the dark cavernous tunnels and chambers of the Elmina Castle through which, in the past, slaves – chained to one other proceeded in a single file from their dungeons to a narrow exit – now called the “Door of No Return”. From there, they went to waiting ships which would take them across the Atlantic to the New World or the Americas and Caribbean. While the slaves were held in the dungeons, the upper floors has spacious suits to house the other occupants of the castle, which during its heydays included the governor, chaplain and treasurer, medical officer, warehouse keepers, accountants, auditors, regular soldiers and ad hoc recruits. The more senior the person’s rank was the higher his accommodation was on the four storied castle building. From the church and the museum, I went to the “Palaver” or the “Bargaining Hall” where slave sellers (middle men) and buyers haggled over the price of slaves or where slaves were sold to the highest bidder through an auction. After slavery was abolished the castle continued to be used as a seat of the administration and as a prison. I walked along the seaward battlement to reach the bastion where the British has once imprisoned the famous King of Ashanti tribe, fabled for their wealth in gold, in 1896 – 97, before he and his followers were exiled to Freetown in Sierra Leone. The king eventually returned in 1936 to resume his role as the leader the Ashanti People. From there I proceeded to the left side of the castle on the top floor to catch a panoramic view of the fishing zone by the Benya Lagoon that I had visited earlier, teaming with fisher folks engaged in catching, buying and selling fish. I could see spectacularly colorful rows of Pirogues or traditional Ghanaian fishing boats. From there, I headed to the last point in my tour of the castle, the Governor’s residence. It was late afternoon. At the spacious and now empty Governor’s residence high up on the castle, I paused for a few moments by a large open window overlooking the ocean. Vast expanses of tender stillness, deep blue Atlantic ocean meeting the sky at the distant horizon, the gentle breeze, open blue sky with soft cotton like clouds drifting by, sea birds in flight, fishermen in their colorful fishing boats casting their nets, swaying palm trees by the shore, waves crashing on the massive boulders, children playing on the beach – I saw incredibly beautiful, profoundly meaningful, poignant and unforgettable symbols of freedom everywhere. At the same time, I was reminded that the deep dark dungeons below, which now lay cold and silent, once reverberated with the footfall of slaves, with the echoes of the deep sighs of despair and cries of human anguish, with disease, death and decay. I was reminded what it meant to be a free human being. I was reminded of what freedom should mean to every other person and thus of my own obligation towards my fellow human beings. (Concluded)

Part III: Echoes of Anguish and the Meaning of Freedom – A tour of the Elmina Castle

Filed UnderAfrica Travel and Adventure