**********************************************

“It was sad that the Paradesi Synagogue was long past its days of glory and splendour. It had been a mute witness to the rise and eventual inevitable decline of the Jewish community and heritage of India. A major symbol of India’s cultural, ethnic and religious diversity was rapidly fading into the sunset, I realized…..”

************************************************

***************************************

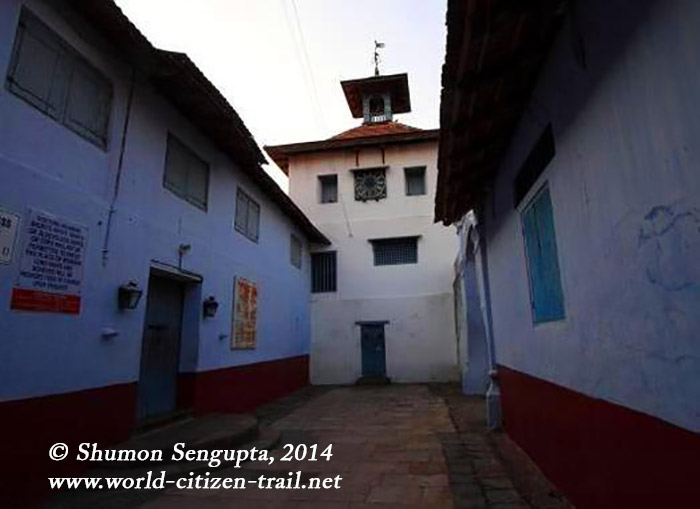

The clock tower and part of the Synagogue seen from first floor of the adjacent Dutch (Mattancherry) Palace….

***********************************************

Our “15-day Kerala Experience” with Compass India Inc. had something amazing in store almost every day. After all, we were in “God’s Own Country”.

In my previous post, I wrote about the Dutch palace with its fabulous murals. In this post, I invite you to come along with me to the adjoining Jewish Synagogue – called the Paradesi Synagogue, at the corner of Jew Town.

But before I take you to the Synagogue complex and the Jew Town in which it is located, some explanation on the Jews of Kochi would be in order.

The clock tower and part of the Synagogue seen from first floor of the adjacent Dutch (Mattancherry) Palace

The Jews of Kochi:

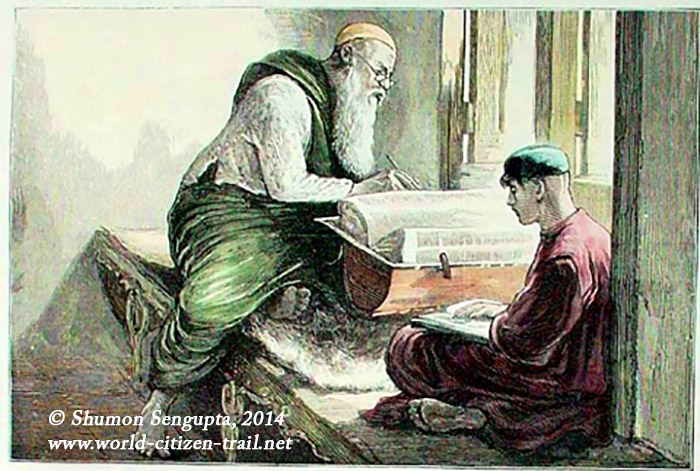

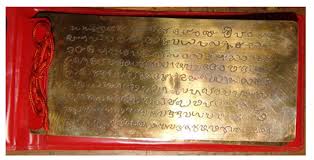

It is not clear exactly when the Jews first started arriving on the Malabar Coast of Kerala. However there is evidence that a formal Jewish settlement existed in Cranganore (presently Kodungallur), about 29 KMs north of Kochi, from the early 12th century onwards. There is some evidence (copper plate inscriptions) which indicate that these early Jewish immigrants were given land and a set of rights and privileges in 1100 CE (Common Era or AD), by Bhaskara Varman Thiruvadikal – the Chera Emperor of the then greater Chera Kingdom of Kerala.

These Jews from Kodungallur are said to have then moved to Kochi in 1341 CE, when a massive flooding of the Periyar River resulted in the siltation of the port in Kodungallur.

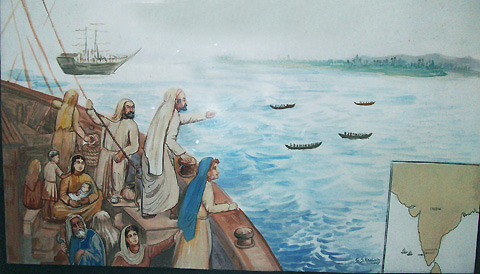

The very first Jews arriving on the Malabar Coast – Painting by S.S.Krishna (Gallery at the Synagogue). Photo Source: http://jewsofcochin.blogspot.com/2011/10/paintings-in-paradesi-synagogue.html

Construction of Cochin Synagogue next to the Maharajah’s palace and temple in 1568, Artist S.S.Krishna. Photo Source – http://jewsofcochin.blogspot.com/2011/10/paintings-in-paradesi-synagogue.html

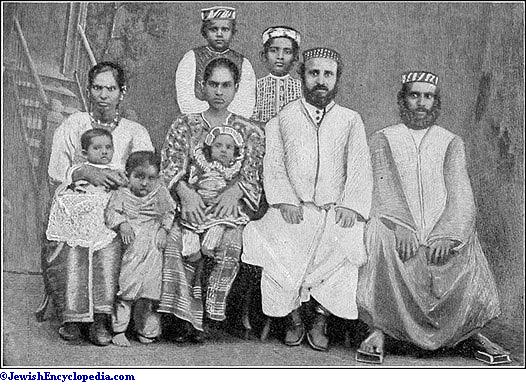

The Malabari, or the so called “Black” Jews of Kochi:

By the 16th century CE, these older Jews from Kodungallur had inter-married with the dark skinned natives and looked no different from the latter. They were called the Malabari Jews – also referred to as “Black Jews” in written accounts of western visitors, although strictly speaking, in racial terms, they were “brown” and not “black”. The Malabari Jews spoke a Judeo-Malayalam tongue.

The Paradesi or the so called “White” Jews of Kochi:

Then, in the early 16th century, following their expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula (mainly Holland, Spain and Portugal) a few families of Sephardic Jews eventually made their way to Kochi. Many of them are said to have come by the way of Aleppo, Constantinople and the land that is now known as the State of Israel, to Kochi.

They formed the Paradesi (meaning foreigner, in many Indian languages) community of the Kochi Jews. They spoke the ancient Sephardic language of Ladino. In Kochi, these newcomers from Iberia were given land by the local ruler – Raja Rama Varma (not to be confused with the earlier Chera Emperor who had given land to the earlier Jews in Kodungallur) to build a settlement and a Synagogue. The land granted was adjacent to the palace of the Raja of Kochi.

In the late 19th century, a few Arabic Jews from Baghdad, and some others from Persia and Germany also immigrated to India. In Kochi, these Jews joined the ranks of the Paradesi Jews. Collectively, the Paradesi Jews, because of their lighter skin colour, also came to be referred to as the “White Jews”.

The Meshuhrarim or “Slave” Jew:

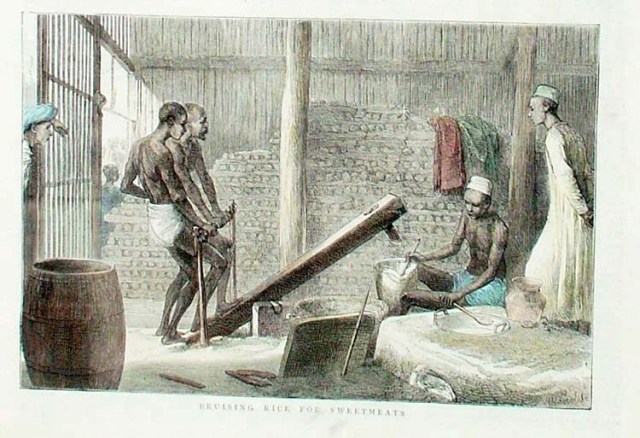

And then, there was the third category of Jews in Kochi – the “Slave Jews” or the Meshuhrarim Jews. Meshuhrarim means manumitted or freed slaves in Hebrew. The “slave Jews” were most probably natives, who did the menial work for the wealthy Paradesi Jews and were eventually converted into Judaism by their masters. Subsequently they were freed by their masters from bonded labour.

Early 18th century painting, depicting “Slave Jews” at work .. The supervisor (on the right, in a white flowing robe) is clearly a Paradesi Jew. These slaves (more like bonded labourers) were subsequently freed and cam to be known as the Meshuhrarim Jews of Kochi.

Although the Meshuhrarim Jews had converted to Judaism following the Jewish law regulating conversions, they did not enjoy the rights other Jews did and were clearly outcastes. This third group therefore soon broke away from the community of their former masters and formed a congregation of their own.

However as the number of Meshuhrarim Jews dwindled over the years (reportedly because of a plague), they no longer had the numbers to maintain their own congregation. They returned to the Synagogues of their former masters (the Paradesi Synagogue), albeit as third class citizens.

Social stratification:

There was considerable social distance between the Paradesi Jews, the Malabari Jews and the Meshuhrarim Jews, pretty much like the Hindu caste system or more like the apartheid if you like. The Malabari, Paradesi and the Meshuhrarim Jews of Kochi had separate synagogues to begin with.

There was considerable social distance between the Paradesi Jews, the Malabari Jews and the Meshuhrarim Jews, pretty much like the Hindu caste system or more like the apartheid if you like. The Malabari, Paradesi and the Meshuhrarim Jews of Kochi had separate synagogues to begin with.

At one point in time, there were seven Synagogues in Kochi, but as the number of Jews in Kochi dwindled, many Synagogues were closed down. The Paradesi Synagogue is the only one which is still in operation.

I shall write about the fascinating history of the Jews of Cochin at some length in a subsequent post.

The Paradesi Synagogue:

Located at the corner of Jew town, the original Synagogue was built by the Paradesi Jews in 1568. It was destroyed by the Portuguese (the most intolerant lot amongst the European colonialists) in 1668 and restored by the Dutch few years later. The Synagogue complex has four buildings enclosed within the compound walls.

The Synagogue is exceptional in many ways, apart from being the most beautiful and the oldest (over 445 years) one functional in the Commonwealth of Nations. It is located next to the Dutch palace (about which I have written in the earlier post). The Palace temple and the Paradesi Synagogue complex share a common wall.

I shall describe the fascinating Jew Town in some detail later, but right now let me describe the clock tower attached to the Synagogue and then the Synagogue itself.

The Clock Tower:

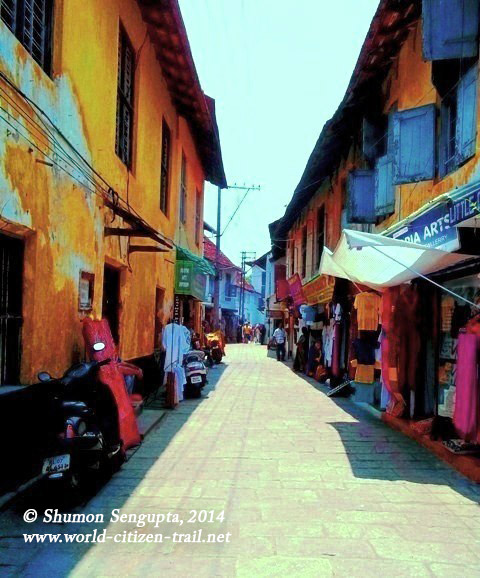

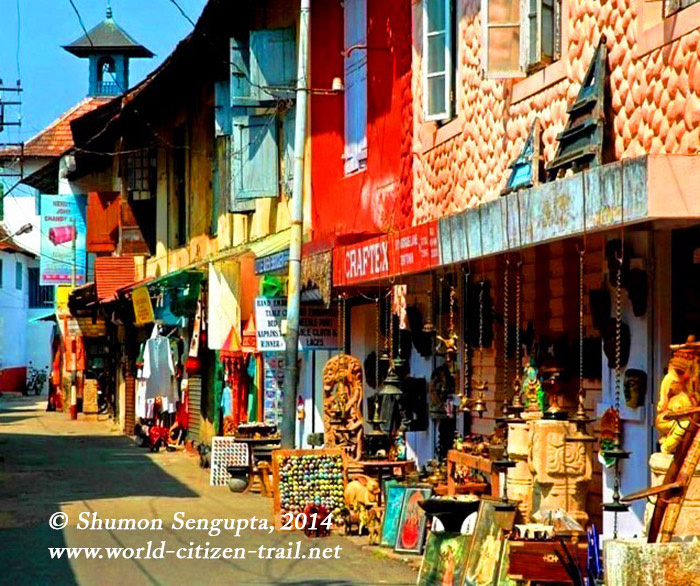

A narrow lane (called the Jew Street or the Jew Town Street) lined with curio shops leads to the Synagogue complex. We could see the top of the clock tower from far end of Jew Street and as we approached the Synagogue complex, we were transported into a strange and beautiful old world.

Jew Street leading to the Synagogue.. the Clock tower attached to the Synagogue can be seen at a distance in the background.

We walked into the forecourt of the Synagogue, face to face with the charming old-world clock tower, with the Synagogue to our left. It is the same structure that we saw from the upper floor of the Dutch Palace, as I had mentioned in my earlier post on the palace. From outside, the Synagogue complex looked very basic – white washed and rather austere.

This Dutch-style clock tower – a later day appendage to the Synagogue was built by the Dutch East India Company’s principal merchant in India, Ezekiel Rahabi in 1760 and it is said that till 1930, the clock used to strike every hour to keep time. The bell at the top is very unusual because unlike Hindus, Buddhists and Christians and like Muslims – Jews, I understand, don’t have the ritual of ringing bells or gongs – not in their place of worship at least.

This Dutch-style clock tower – a later day appendage to the Synagogue was built by the Dutch East India Company’s principal merchant in India, Ezekiel Rahabi in 1760 and it is said that till 1930, the clock used to strike every hour to keep time. The bell at the top is very unusual because unlike Hindus, Buddhists and Christians and like Muslims – Jews, I understand, don’t have the ritual of ringing bells or gongs – not in their place of worship at least.

The clock tower was painstakingly restored in between 2001 and 2006 by the World Monument Fund. The restoration work included repairing damaged masonry work and replacement of decayed structural elements of the teak-framing system. The clock tower was also cleaned and painted and the missing parts of the mechanical clock were replaced. Also the large brass bell, which was lying on the floor for years, was reinstalled at the top.

About 45 feet and three stories tall, the clock tower has four faces, with dials (made of teak and painted in blue) on three faces. To the north, facing the Dutch Palace, the numerals are in Malayalam. This was meant for the Raja of Cochin to read from his palace. To the south, viewed from Jew Street, the dial has Roman numerals. To the west, from the synagogue side, the dial has Hebrew numerals. The fourth side of the tower is blank. The original entrance to the Synagogue was from the west and that entrance is now closed.

About 45 feet and three stories tall, the clock tower has four faces, with dials (made of teak and painted in blue) on three faces. To the north, facing the Dutch Palace, the numerals are in Malayalam. This was meant for the Raja of Cochin to read from his palace. To the south, viewed from Jew Street, the dial has Roman numerals. To the west, from the synagogue side, the dial has Hebrew numerals. The fourth side of the tower is blank. The original entrance to the Synagogue was from the west and that entrance is now closed.

The Synagogue complex is a rectangular building, with white and yellowish-brown walls and sloping tiled roof. It has wrought iron gates, bearing the Star of David and the candelabra.

Inside the Synagogue Complex:

The Paradesi synagogue complex, in addition to the clock tower and the main worship hall, has various other connected rooms or spaces. Not all are in use though.

From the narrow forecourt below the clock tower, we entered the inner courtyard, through a doorway to our left. From there we approached the first inner room, or the foyer of synagogue. From there, through another doorway in the wall connected to the clock tower, we walked through a small corridor that led us to a longish, rectangular room on the right. This room used to be a store in the past, but today it houses a gallery that recounts the history of the Synagogue through a series of large framed canvases.

Gallery Depicting the History of the Synagogue:

(Photo Source: http://jewsofcochin.blogspot.com/2011/10/paintings-in-paradesi-synagogue.html)

This gallery was commissioned to mark the 400the anniversary of the construction of the Synagogue and paintings were executed by S.S.Krishna, a local artist. The large paintings, which are now partly faded, depict the landing of the first Jewish settlers in the Malabar Coast and their subsequent history.

There are many versions of the history of the Cochin Jews and this gallery depicts the story according to which the copper plates were issued by the Chera Emperor in the 12th Century to a putative ancestor of the Paradesi Jews. This is however hotly contested by the Malabari Jews who claim that their ancestors were the recipients of the copper plates.

True or otherwise, we appreciated the narration of the Paradesi version of the history through the series of large paintings.

From the gallery, we got back to the foyer and from the foyer into the spacious main prayer hall. We had to take off our shoes before we entered to protect the special flooring of the main hall.

Hand-painted Ceramic Tiles from Canton, China:

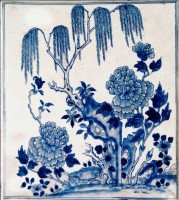

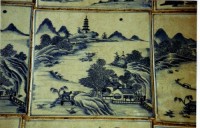

I found the floor of the large prayer hall of the Synagogue to be a striking contrast to the ornate interiors of the hall. The floor was paved with hand-painted blue, willow patterned ceramic tiles. These tiles were imported from Canton, China in 1762 and it is said that there are 1,100 tiles consisting of four different basic patterns. Of course, since these tiles were hand painted, each had to be unique. I found these tiles to be rather enigmatic and they seem to convey something, about which I had no clue. Later I learnt that they were indeed symbolic.

According to ceramic experts Gonneke en Jaap Stavenuiter and Trudy Laméris-Essers, “the pattern is composed of horizontal rows of tiles with a repeating design. There are four different designs, that of the first row being identical with the fifth, the second with the sixth, and so on”.

“The bottommost row depicts a lotus and prunes, which symbolize summer and winter, and at the same time express a contrast such as that between man and wife in marriage. The tree peony on these tiles points to love and is considered a good omen. The row of tiles above shows a chrysanthemum together with a willow and boulders. Chrysanthemum and willow symbolize autumn and spring, another contrast between husband and wife in marriage. The rocks symbolize fidelity and a long life. In the third row we see a tree peony and a boulder, together representing the queen of flowers. It is a sign of good fortune, to be relied on forever. Finally there is a row of rural scenes with a familiar willow pattern. It is a moot point whether the images of the tiles in this synagogue were intended symbolically, considering that a synagogue is the place where marriages are solemnized”.

summer and winter, and at the same time express a contrast such as that between man and wife in marriage. The tree peony on these tiles points to love and is considered a good omen. The row of tiles above shows a chrysanthemum together with a willow and boulders. Chrysanthemum and willow symbolize autumn and spring, another contrast between husband and wife in marriage. The rocks symbolize fidelity and a long life. In the third row we see a tree peony and a boulder, together representing the queen of flowers. It is a sign of good fortune, to be relied on forever. Finally there is a row of rural scenes with a familiar willow pattern. It is a moot point whether the images of the tiles in this synagogue were intended symbolically, considering that a synagogue is the place where marriages are solemnized”.

(Source:http://jewsofmalabar.blogspot.co.uk/2011/09/mysterious-tiles-of-paradesi-synagogue.html)

Stylistically, initially I felt that the Chinese tiles were at odds with rest of the building and its interiors. Nevertheless, by themselves, the tiles were exquisite and subsequently I realized that along with European, Middle East and Indian design influences, these tiles gave the hall a beautiful, eclectic and unique look.

Stylistically, initially I felt that the Chinese tiles were at odds with rest of the building and its interiors. Nevertheless, by themselves, the tiles were exquisite and subsequently I realized that along with European, Middle East and Indian design influences, these tiles gave the hall a beautiful, eclectic and unique look.

Belgian Chandeliers and the Brass Pulpit:

There were two rows of chandeliers along the length of the prayer hall and an array of colorful, but simpler and smaller inverted dome shaped chandeliers along the width of the hall on the rear. Many chandeliers, we were informed, were of Belgian origin. Near the center of the hall, we found the raised pulpit with beautiful, tall brass railings. Understandably, we were not allowed to step into the pulpit.

There were two rows of chandeliers along the length of the prayer hall and an array of colorful, but simpler and smaller inverted dome shaped chandeliers along the width of the hall on the rear. Many chandeliers, we were informed, were of Belgian origin. Near the center of the hall, we found the raised pulpit with beautiful, tall brass railings. Understandably, we were not allowed to step into the pulpit.

The Wooden Arc and its Hidden Treasures:

Ahead of the pulpit on the opposite wall, we found an intricately carved wooden ark that houses four scrolls of Torah (the first five books of Old Testament) and these scrolls are said to be encased in silver and gold. Two priceless gold crowns presented to the Jewish Community by the Kings of Kochi and Travancore are also said to be kept here. Old copper plates from the 12the century, with inscriptions describing the rights and privileges granted by the erstwhile Chera Emperor to the Jews, are also said to be housed in the synagogue.

Ahead of the pulpit on the opposite wall, we found an intricately carved wooden ark that houses four scrolls of Torah (the first five books of Old Testament) and these scrolls are said to be encased in silver and gold. Two priceless gold crowns presented to the Jewish Community by the Kings of Kochi and Travancore are also said to be kept here. Old copper plates from the 12the century, with inscriptions describing the rights and privileges granted by the erstwhile Chera Emperor to the Jews, are also said to be housed in the synagogue.

We were told that there is a hand knotted “oriental” rug, which was a gift from Haile Selassie, the last Emperor of Ethiopia.

Since none of these were on display, we could not see them – only heard about them from our guide. The management of  the Synagogue, for some reason, seemed to be rather keen on holding back things. Of course there might be a security risk and that is understandable I guess. Nevertheless, for a history buff and an antiquarian like me, it was a bit of a disappointment. I would have loved to see the copper plates and the Torah scrolls at least, if not the “Oriental” rug as well.

the Synagogue, for some reason, seemed to be rather keen on holding back things. Of course there might be a security risk and that is understandable I guess. Nevertheless, for a history buff and an antiquarian like me, it was a bit of a disappointment. I would have loved to see the copper plates and the Torah scrolls at least, if not the “Oriental” rug as well.

Women’s Gallery:

At the rear of the hall, just above the rows of colorful little chandeliers, there was the exclusive women’s gallery / balcony overlooking the main prayer hall below. There was a narrow wooden staircase at the back that led from the main hall to the women’s gallery and we were not, for the right reasons, allowed to climb up to the gallery. From below we could see that the gallery had gilt columns and railings and elaborate wood work. I could visualize traditionally dressed, petite Paradesi ladies, perched on the top, looking down into the prayer hall and listening to the service. The vision was charming.

Wood and Wicker Benches:

The prayer hall had beautiful, quaint, faded wooden and wicker benches on the right and left flanks. It also had two rows, back to back in the middle and two rows, side by side, at the rear and front of the hall for worshippers. Besides, there was a single row of wooden benches on the two sides, across the length, just below the large windows.

In the past, only the Paradesi Jews had full membership of the Synagogue. The Malabari Jews could worship in the Synagogue, but were not formal members of the congregation. While both the Paradesi and Malabari Jews could sit on these benches and pray, the Meshuhrarim Jews did not have any communal rights and had to sit on the floor or the steps outside while worshipping at the Synagogue. They were the subalterns, if you like, amongst the Cochin Jews.

More about that, I shall share in another post in which I will provide a brief account of the history of the Kochi Jews…

We spent some time admiring the interiors of the Synagogue. It had an incredible old world charm about it, apart from being very peaceful. Natural light coming in through large open windows reflected on the colorful inverted dome shaped chandeliers. It was beautiful.

Way out:

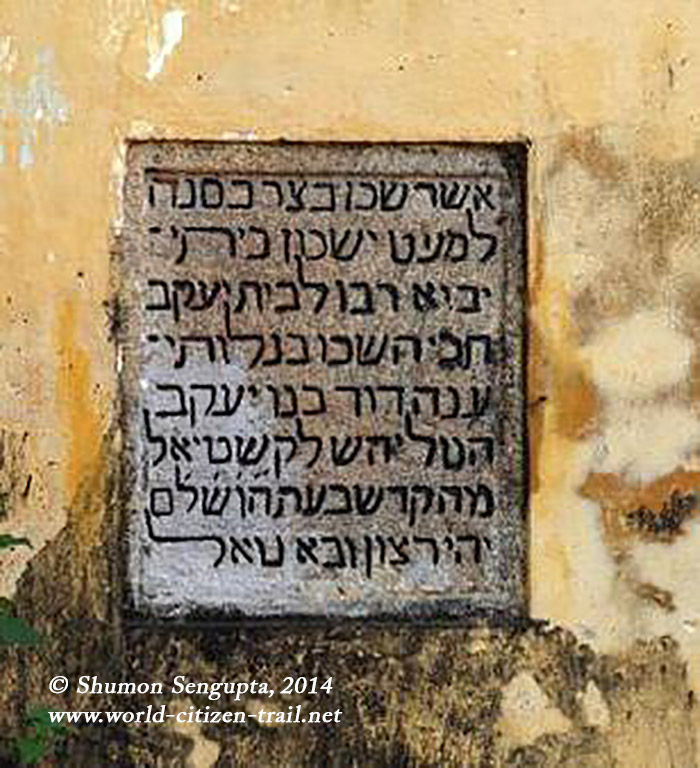

While going out, we found a stone tablet from an earlier synagogue that was built in Kochangadi in Cochin in 1344 but later destroyed, placed on the outer wall of the synagogue. Adjoining the Synagogue was the Jewish Cemetery, with tomb stones inscribed in Malayalam and Hebrew.

While going out, we found a stone tablet from an earlier synagogue that was built in Kochangadi in Cochin in 1344 but later destroyed, placed on the outer wall of the synagogue. Adjoining the Synagogue was the Jewish Cemetery, with tomb stones inscribed in Malayalam and Hebrew.

In 1948, there were around 3,000 Jews in Kochi. With the formation of the State of Israel around that time, most of them went away to their promised land. Today, only eight elderly Paradesi Jews from seven families remain in Jew Town and it is said that about forty more practicing Jews live in adjoining Ernakulam. The old villas of the Jews who left are now occupied by a different people – many of these homes converted to curio shops and other stores. Some are dilapidated and crumbling.

I was told that often, the weekly prayer service at the Synagogue cannot be conducted due to an inadequate number of male members – the quorum of 10 male members required for a Jewish prayer service.

We left the beautiful Synagogue, with a strange feeling. As I walked out into the street, I realized that the Jewish heritage of Kerala, although now reduced to mere history, spoke volumes about the remarkable large heartedness of the erstwhile local rulers. These rulers of Kerala not only gave the Jews, persecuted elsewhere all over the world, protection and a place to settle, but also granted them religious, social and economic freedoms. It made the heart go warm and I thought it was a great lesson from history for contemporary India.

At the same time, it was sad that the Synagogue was long past its days of glory and splendour. It had been a mute witness to the rise and eventual inevitable decline of the Jewish community and heritage of India. A major symbol of India’s cultural, ethnic and religious diversity was gradually fading into the sunset I realized…

With mixed feelings, we make our way into Jew Town, at the edge of the Synagogue …

About that in my next post…